I’m an old programmer as these things go. One of the best things I provide is perspective. You’re probably thinking that means I’m going to reminisce about the good old days. But I think the good old days are hilariously overrated.

HTML-based GUIs get a lot of flack for being a cheap-to-build imitation of native-app. This is basically true. It’s a cheap imitation, so we can build (and test!) a lot more with a small team, for cheap. In return, they burn a lot more CPU and memory, which is sometimes okay and sometimes not. I’m building something like that right now, so obviously I think it has good points.

But I think the biggest advantage of HTML-based GUIs isn’t usually mentioned: testability.

Wait, What are Native GUIs Again?

First question: what’s the alternative to building a GUI as a little HTML-and-JS web app?

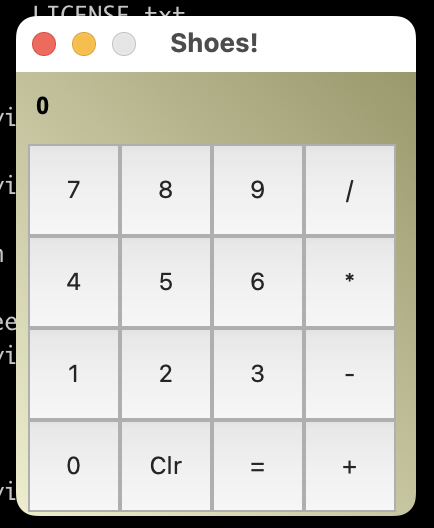

You can make a native GUI – something based on ObjectiveC or Swift on iOS, or based on Java and Dalvik on Android (or similar libraries, in both cases.) On the desktop you can write something based on Cocoa on Mac or GTK+ or KDE on Linux, or Windows UI on Windows. There are numerous wrapper libraries for all of these. Some wrappers are cross-platform like WxWindows or FLTK. Some are single-platform, like using VCL for Windows.

In all of these cases, they create windows and buttons and drop-down selectors and whatnot (collectively “widgets”) using native calls for your operating system of choice. They do not run a web browser. As a rule this makes them smaller and lighter in terms of how much CPU, how much memory and how much disk space they require. It’s still possible to screw this up even if you don’t run a web browser, but a browser nearly guarantees heavyweight apps (and/or dependence on the user installing a big program like, say, Google Chrome.)

Native GUI libraries have functions (or methods) you can call to create elements like windows or buttons, to set properties like images and text, and generally to manipulate them. Whatever a native application can do, the native UI libraries can do. Whatever the most efficient way to do a thing is, the native UI libraries can do it. That’s part of why really good native apps are so good. A skilled MacOS specialist can build you an unbeatable MacOS program. Somebody who really knows Android can beat a ported app by a mile, though it’ll cost a lot more to write it and to maintain it.

How Do You Test Native Apps?

I’m an old guy. I remember when there wasn’t much automated testing, and you used big teams of people to poke around the app every time you made a new build, and make lists of what was wrong. Larger companies and harder-to-test apps still have to do this, and you basically always want to do some of it. But it used to be the way everything was tested. It’s expensive and inefficient, but all of app development used to be a lot more expensive and inefficient. It wasn’t the worst thing we did, I promise.

You could find automated testing libraries for GUIs. They tended to be really ugly and fragile. That’s partly because it was (and often is!) so hard to tell an operating system “load this application and then tap in this spot, just exactly as if a user had done it.” Accessibility APIs are slowly helping this, but there’s a reason you see so many complaints about accessibility – companies treat it as an afterthought. And if the OS does that, everybody else is building on a cruddy API. Oopsie? It’s the best it’s ever been, but still not great. These days you can sometimes only have your app break when you actually change the widgets, not every time you resize a window.

You can also write a sort of wrapper layer around the GUI library, so that you can insert clicks and hovers and keypresses just like the OS. Another layer of abstraction can work wonders here.

Hey, remember when I said the big reason to use a native app was because you could do everything the OS could possibly do, as fast as it could do it? You know what screws that up? Another layer of abstraction.

So: adding layers of abstraction to make native apps easier to test isn’t very popular with the native app crowd. You’ll see it happen, but it’s been an uphill fight. Given how much extra you pay developers to write good native apps, you can see why they don’t like it.

I mentioned that automated testing libraries tend to be fragile. That’s because at the OS level, you don’t really know what the app is doing. Maybe the app draws its own windows and buttons (more common than you’d think!) You can say something like “click 150 pixels right and 50 pixels down from the upper-left corner of this window.” But then if the widgets move, or if the window opens partly offscreen, your tests may randomly break. You can also solve this with more layers of abstraction, which are unpopular, as I mentioned before.

So What’s Different About HTML Apps?

Here’s something interesting about HTML apps: they hate customisation. That’s gonna get some people’s knickers in a twist, so let me explain what I mean.

There’s nothing that stops you from opening a canvas in your web browser and drawing all of your own buttons and frames and containers. In fact, a lot of browser-based games work exactly like that. The accessibility folks will complain (and they really should). But you can do it, no question.

Heck, you can use a Photoshop mockup for your background image and just handle clicks directly in code (“if they clicked with X between 200 and 450, and Y is between…”). You used to see Flash apps do that all the time.

But mostly people don’t. Instead, we tend to use buttons for buttons and divs for containers even when that’s harder than doing it the other way. Partly that’s for accessibility, but it’s also for a lot of other reasons. Browsers change a bit over time, and it’s often really useful for the browser to know that a button is a button so that it can handle it right on iOS or other situations you haven’t tested. Some later developer might mess with CSS on the page and make things hard to see, and the user can go in and hack around that, in several different ways, if your divs are divs and they can use “inspect element” on them.

In an HTML app, you’re almost never drawing things in plain pixels and making them work in plain clicks. You’re drawing divs or buttons or something larger and more coherent.

You have an abstraction layer, the same kind I mention native app people hating. It makes it easier to test, because pixels and clicks are really hard to test, but if it’s all done in button clicks and window resizes, it’s much easier to write an assertion like “somebody clicked on a button marked ‘OK’” or “if the window resizes to double size, the button stays the same size”.

In theory you can do this with an abstraction layer under a native UI toolkit. I’ve worked with those abstraction layers, and they do help. You can write a wrapper around the native UI API and get a fair percentage of that benefit, though not for everything.

Also, in theory you can do everything HTML-based inside a canvas, or otherwise do it all yourself. HTML makes that really awkward, so mostly people don’t. But it happens, especially for games. You can write a nearly untestable browser app, but it’s usually more work for every part of the app, not just testing. I consider that to be good design by thoughtful people. You may have a different opinion.

But That’s Only the Second-Best Reason

The fact that HTML apps come with a strong built-in abstraction layer is good. But there’s actually an even better reason that they’re more testable: HTML itself.

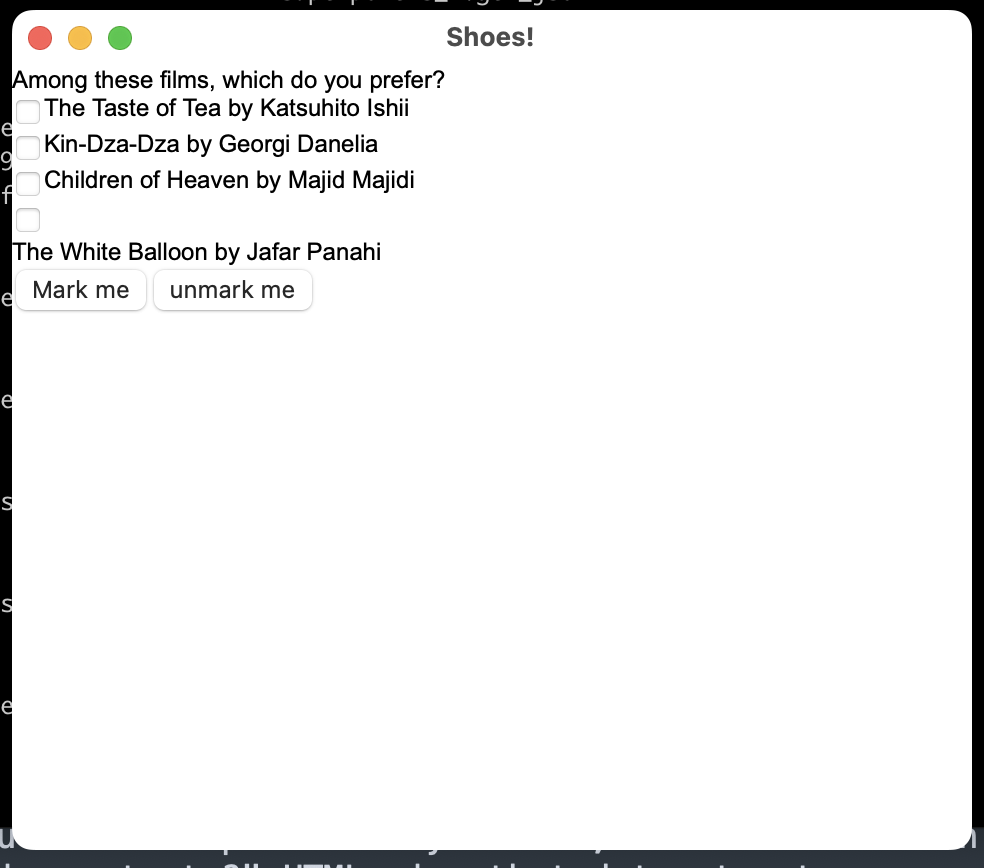

A web page automatically has the ability to take a tree of widgets (frames, buttons, drop-downs, etc) and turn it into a chunk of text. That’s what HTML (and JS and CSS) does. It’s not perfectly one-to-one, so you may have to account for differences in quotes or whitespace between two identical pages. But you never stop and ask yourself, “how would I turn this into a data structure I can double-check in my tests?” HTML is that data structure.

And so HTML testing frameworks basically always let you grab a chunk of the page as HTML (e.g. grab innerHTML from a div) and check for things like “is there a drop-down selector under this div?” or “can I find the text ‘Launch Doomsday Device’ in the HTML for this button?” That’s not really a thing in a native GUI.

You could build it. If you built a serialisation format for widget trees (that’s what HTML does here), you could do a very similar thing with native windows. Something like “<window width=‘1100’ height=‘600’><button text=‘OK’ /></window>” and so on. That is, you could mimick HTML. Of course, HTML already implicitly knows when you’ve manually selected something (a width, say) versus let it choose the defaults. The web browser UI is literally designed around its serialisation format, HTML. And so the serialisation format isn’t an afterthought. It’s the central part of the whole design, and support for it is unparalleled.

You could build a serialisation format for MacOS windows, or for Android UI screens. But you wouldn’t have the giant ecosystem of parsers, validators and so on that make HTML so (relatively) testable.

I spend a lot of time in Ruby on Rails. And if you talk to Rails folks about how testable HTML is, they’ll probably laugh until they snort. For Ruby on Rails code, HTML and Javascript UIs are ugly and poorly behaved.

That’s because they’re about a quarter as ugly and poorly behaved as native UI libraries. They’re mostly tame and testable by comparison. Which makes them about a quarter as tame and testable as, say, Rails model tests or “plain and simple” unit tests with no GUI attached.

Testing with Selenium or Capybara isn’t the most fun thing in the world, especially when you need Javascript to work.

But you have a very solid serialisation format for your entire interface. Even when your Javascript builds a whole new interface at runtime, you can still call “body.innerHTML” and get a serialised version of the whole thing.

And you have a number of major companies building big tools – like browsers – that support all this very solidly.

Native GUI testing libraries are just not in the same class.

But You Can Call Native APIs!

Native GUI testers can, rightly, point out that there are perfectly good testing APIs here. For instance, you can start at the top level of a window and look through all its child widgets until you find the one you want.

This is almost exactly like grabbing a body or frame tag in Javascript and using the DOM-object APIs to look through all its children… without using CSS selectors.

Do you notice how almost nothing in Javascript testing does that? That’s because we have HTML as a serialisation format, and CSS selectors to find attributes and HTML tags (widgets). The tags-and-selectors approach is so much better that we’d never even consider using the raw DOM and iterating through. We’d only do that when building a better API on top of it, because it’s so akward. It feels ugly and primitive.

And that’s the power of a serialisation format that all the tools support.

One More Time

Native GUI libraries are harder to write your app in. In return, they give more control and better performance. The cost difference in writing your app is significant, but not as large as the difference in how hard it is to test native apps compared to HTML-based apps.

Native GUI tools tend to avoid extra abstraction layers, because they’re selling speed and power. HTML-based apps are already wrapped in heavy abstraction layers, so they provide them cheerfully. That makes test APIs a bit smoother.

More importantly HTML-based apps provide HTML itself, a very powerful serialisation format, for the GUI itself. You can always ask a browser-based app to render itself into HTML and then make assertions on that HTML. That means there’s a well-known, well-tested testing API layer that’s common to all HTML-based tools. This isn’t true for writing native GUI libraries, nor for testing them.

It’s common knowledge that browser-based apps are easier and cheaper to write than native apps. It’s not a commonly mentioned that HTML makes GUI testing, which is historically horrible, into something that’s merely somewhat inconvenient.

Comments