In the age of using internet sites for important things – social media, say, or banking – the Internet has grown status pages, to let companies know whether a particular service is currently working.

Companies have always had internal status pages. But these days most have external status pages, so non-employees can tell whether the site is working. First people outside the company started doing that, and then companies realised they couldn’t avoid it happening, so better to provide status pages for themselves.

Why is it so bad for somebody else to provide your status page? What’s different about a company’s official status page?

As I write this there’s an ugly Discord outage which is barely acknowledged on their status page, so it’s a great time for me to talk about that.

Experts Agree, Everything is Fine

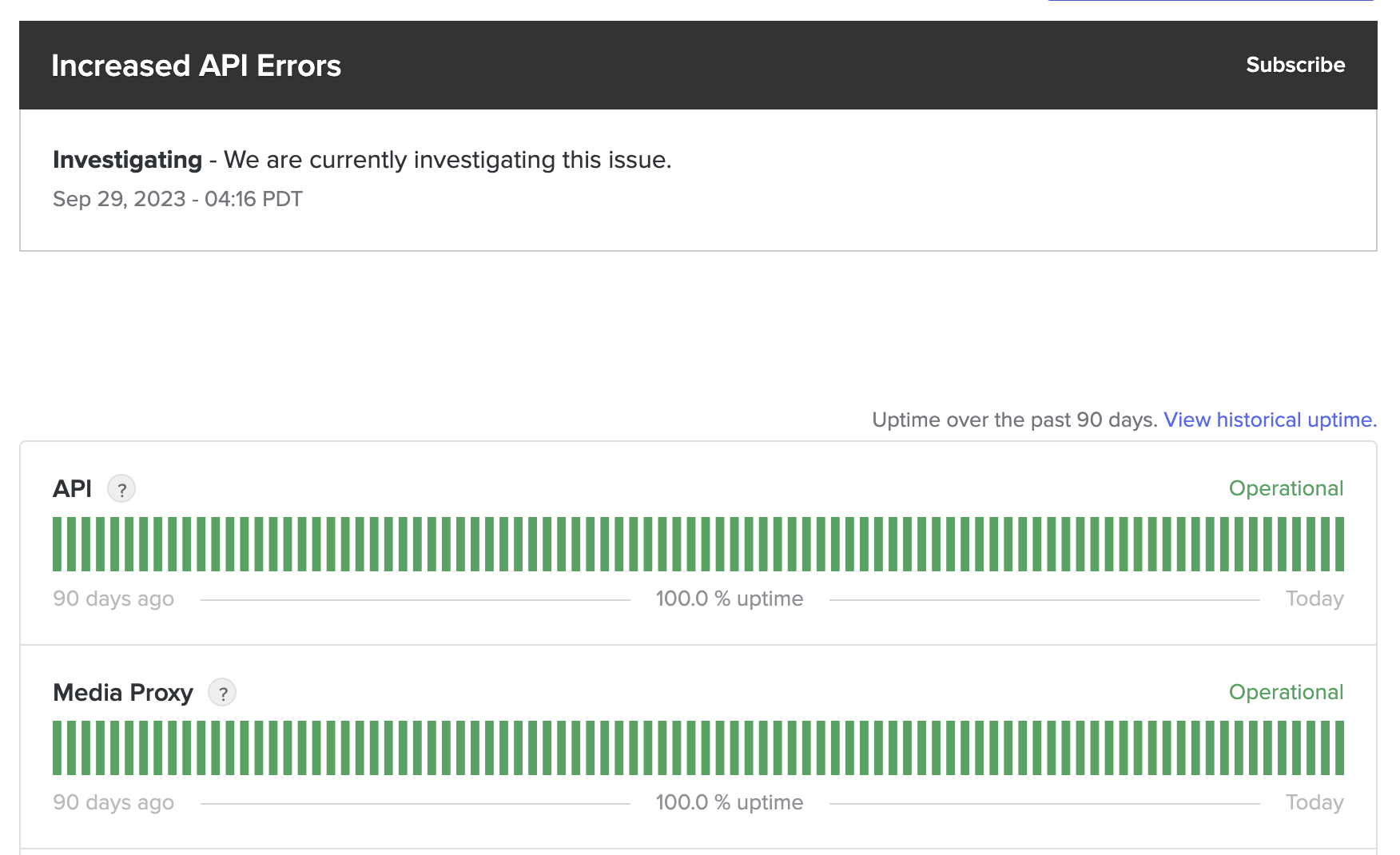

Here’s a weird thing: company status pages tend to far downplay an outage. If people are showing up because they think something is wrong, what advantage do you get from lying to them? For instance, here’s what Discord is showing as of a moment ago:

Notice anything odd? They’re showing an incident with API error rates, but show no changes in the API uptime. So then “error rates are bad, people can’t use it” doesn’t count as affecting the uptime. At all.

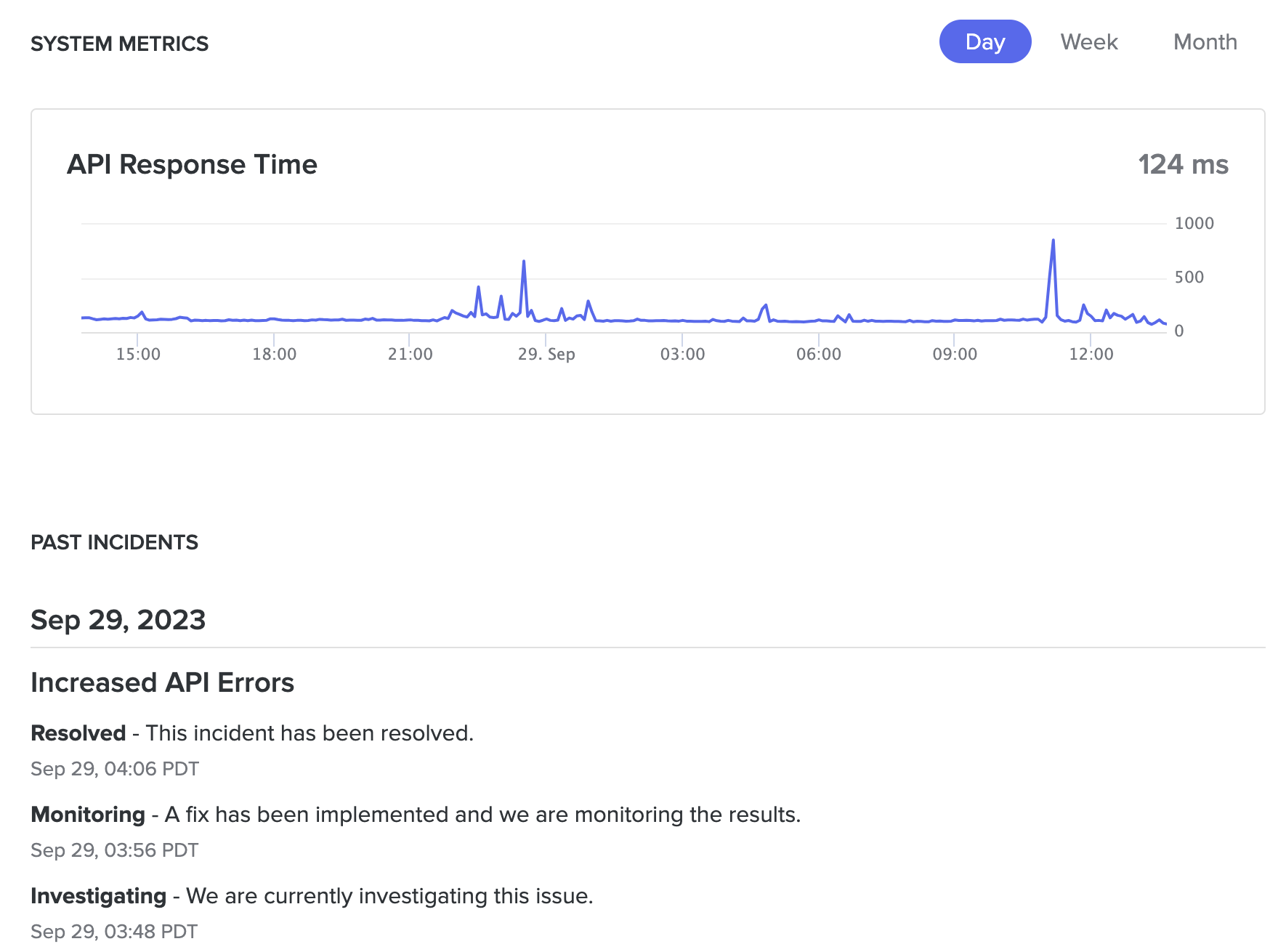

I’m not trying to pick on Discord here. If you look at nearly any company during an outage they do this. They tell you everything is fine, and has always been fine, even mid-outage. They also put up the “we found a problem” notice days or weeks after the problem is found – usually after an article has been published and passed around on social media. They’ll put up a “we solved it, everything is fine” message before it’s solved. Here’s Discord’s “everything is fine” notice, from lower on the exact same page at the exact same time, while at the top it (correctly) says people are having problems:

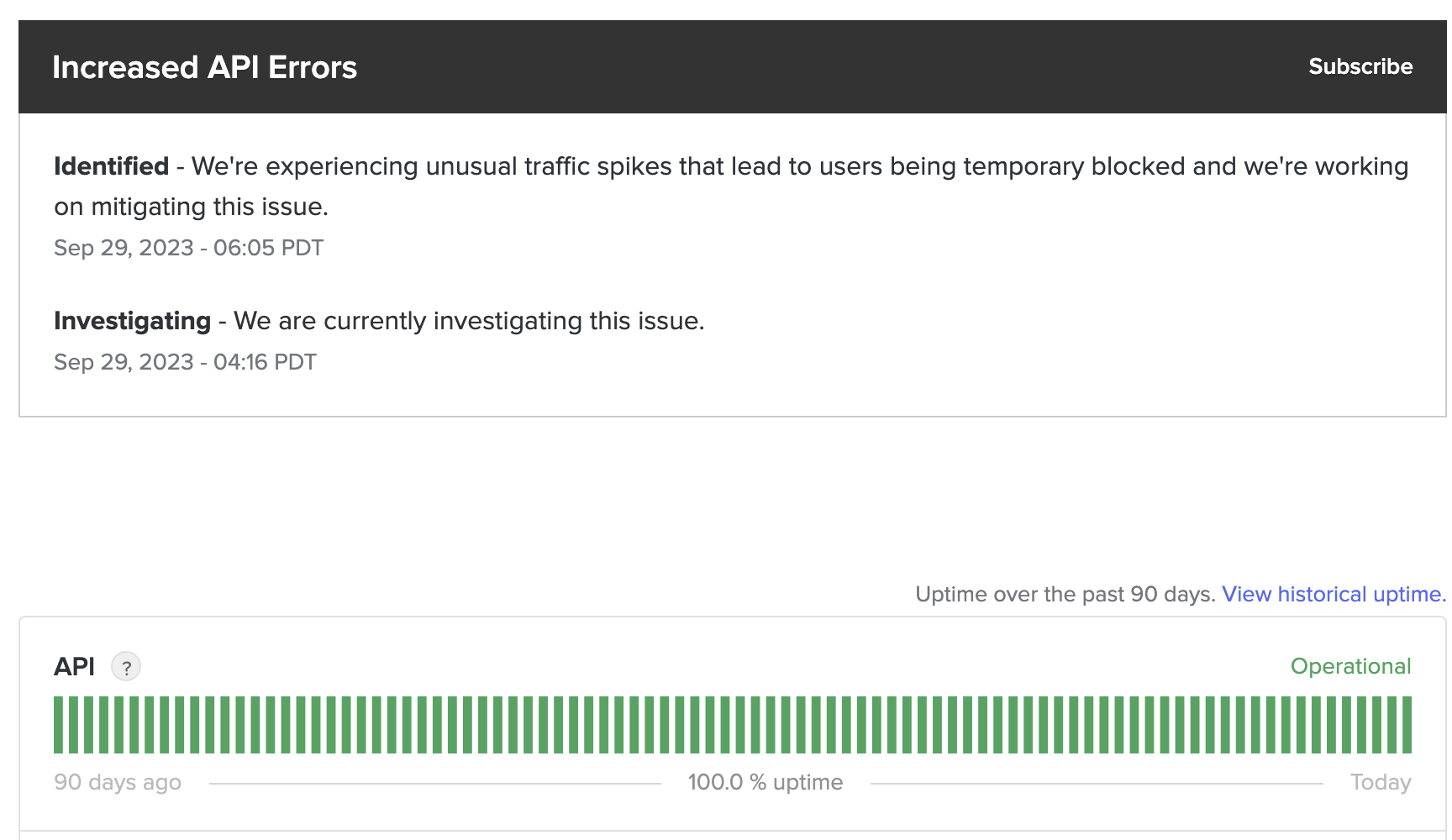

As I wrote this they (finally) put up something acknowledging (some of the) widespread problems with this new update. Of course, it’s in a similar downplaying tone.

People go to this page because they already know Discord is screwing up. They can instantly communicate with a whole world of people to verify that, yes, Discord is screwing up. Third-party status pages like DownForEveryone say that, yes, Discord is screwing up.

Is Discord that oblivious to problems, such that external status pages are that far ahead of their own assessment? Is every company with a status page that oblivious?

Of course not.

Down For Everyone Or Just Me?

The first popular status pages, things like Down For Everyone Or Just Me? did what that sounds like. You want to know if the problem is just you. DownForEveryone is still decent, and things like it often work well. But there’s not a ton of ways to make money providing this service, so it would naively seem to make sense to rely on the company for status information.

SREs are the other big cause of status pages. If you’re dealing with a vendor, and you’re reporting problems, it can be frustrating that they don’t respond to you. And of course they’re not going to give you regular updates – why would they? You’re not their boss. The vendor saying to a customer “oh yeah, we’re not working on that right now” can get people in trouble. It’s much safer to not say anything. In fact, most companies will tell their employees absolutely not to respond to external queries, and send questioners to the PR team, media team or similar.

A status page is a way around that, somewhat. If your operations folks can put up a status page, it gives updates to customers. In fact it tells everybody, and it doesn’t require extra communication during a crisis. You can just leave the status page up and bonus communication happens.

Ops folks and SREs, in my experience, are tactless, direct and pessimistic. Their internal dashboards are accurate and unadorned. They pride themselves on knowing when something isn’t working. Their history graphs are full of blips and ups and downs, showing when there are minor delays, or normal failovers.

Nothing like a public status page, in other words.

So what’s going wrong? Why is the public information so bad? Why is the only permissible status page a wall of green for all time, even during outages?

Liability and Public Relations

I’m checking the status page again now, a few minutes later, and the problem with IP addresses being blocked is gone. No sign it was ever there. It’s still happening, but they’ve replaced it on the page with the “all fixed” problem with API errors. The API error problem still doesn’t show on their graphs and they say it was fully corrected hours ago. But has somehow it has re-opened on a different part of the page.

Discourse is still down, of course. Has been for hours. This is not a case of slightly different points of view. They’re outright lying. The various other third-party downtime detectors are all well aware that they’re having problems, and Discord clearly knows as well.

Here’s the problem: a status page, being public, becomes a weapon of public relations. The company wants to convince you that they’re reliable. They believe that a graph, from them, acknowledging problems, is less okay than them lying constantly through every outage and error.

Presumably they’re right. If every company does it, that’s normally a sign that it’s the right – or at least profitable – thing to do. A “best practice,” as they say in the business.

If you look at these pages, there’s no question. The PR teams have achieved complete victory over the operations teams.

So you can’t trust any of these services to be reliable. If there are any problems, they will lie about them absolutely as much as they can, like Discord posting “minor problems with some APIs” when the site is unavailable for hours.

(All of them? At a minimum, I mean any company with an all-green status page history. But really it’s nearly any tech company. I could mince words about some companies publishing some percentage of the postmortem reports that they promise, but I won’t bother.)

You can’t trust them to be reliable. They clearly believe that lying to you about being reliable, and pointing you at the page full of lies, is the profitable part of “reliability”. This is a nearly universal practice, so the Occam’s Razor assumption is that they’re right.

But the Efficient Market Hypothesis?

You might reasonably say, “how could a whole industry lie about this? Wouldn’t they get caught?” I tend to think of Kyle Kingsbury, a.k.a. Aphyr, and his many-year exposure of how bad the distributed storage industry is. Dan Luu has a great writeup here if you want the details. I was paying attention as it happened – many of us were. We cheered from the sidelines, because it was obvious to many people before him how bad those products were.

The company has every incentive to lie exactly as much as they can get away with. They can get away with a lot. And they do. Why wouldn’t they?

The company has accurate internal views. It could, in theory, put them online. But customers would find it worrying. The companies look much more reliable if they put up a standard wall-of-green status page.

So reliability is only a problem if non-expert, constantly-lied-to customers catch you at lying about it.

If you ever need more reliability than that… mostly you’re out of luck.

But this is the public status page. Surely you can buy special, more-reliable products from companies if you really need to know? In theory, yes. For instance, you could imagine buying distributed storage products from companies whose entire business is providing that safety at scale. And Aphyr reminds us that if there aren’t third parties keeping them honest, they will produce complete garbage and lie about it.

Lying is cheaper than telling the truth. The Efficient Market Hypothesis tells us that, if nobody is keeping them honest, companies that bother to really do the work should be out-competed by companies that take the cheaper “lie on our status page” approach. It’s not on our side here.

An efficient market or company will be efficient at following its incentives, not necessarily at doing something you want.

But Why Do We Care?

You could say, “yeah, sure, companies talking in corporate spin, news at 11.” Which is true.

But here’s the thing: your value as a software developer depends on keeping things working. If companies – if vendors – can’t be relied on to do that because their incentives put them in an ugly spot, that’s important for you to know. Yes, companies talking in spin, news at 11. Yes, companies being unreliable and lying to you about it, news at 11.

But that means you need to plan as though that were true.

Since your value depends on keeping things working, and keeping things working is harder than advertised, it’s important for you to think through that. How can you do more for yourself? How can you do more with components you can validate for yourself?

You can’t trust companies, or even industries, to tell the truth here. The Efficient Market Hypothesis is not coming to save you. You’re going to have to actually think through this for yourself.

Because otherwise, your work doesn’t keep working. And the value you promised doesn’t materialise.

I don’t want to be in the business of fooling suckers into paying me more than I’m worth. I want to be in the business of selling value. And living in a world like that takes understanding. Let’s keep looking for understanding together.

As I finish writing this, Discourse is back to acknowledging the blocked IP address problem. All the bars still show 100% reliability for the last 90 days, of course. Technically push notifications shows only 99.99% uptime. I’m not sure why they allowed that one graph, near the bottom, to show a 0.01% imperfection during a complete outage. Perhaps that manager drew the short straw.

Am I picking on Discord? Not really. I’m taking out my frustration on our entire industry as they “just follow best practices.” Discourse is not worse than the rest. And that’s the problem.

Comments