I’ve been fortunate to work in DevOps and with great Ops folks in my career, including doing enough of that work to get a feel for it. The tools are fun and it’s nice to be able to do basic tasks, but the incredible, invaluable thing was just watching how experienced OpsFolk responded to different events.

It’s not just the smooth, immediate way that they handle warnings and outages, though that is impressive. It’s also their basic understanding that new features, even features meant for robustness and resilience, are basically trouble. It’s not that an undisturbed system will necessarily keep working… But a system you disturb will invariably develop problems of some kind. Deployments tend to break things, and deploy-free weeks like holidays tend to be downtime-free.

But the important part isn’t the fact that they’re right. The important part is seeing a completely different attitude toward the software we write. Our way is valid for what we do, their way is valid for what they do, but it gives us completely different principles (that is, “unwritten rules that underlie everything we say and do”) about software.

Just like “everybody else has an accent,” it feels like everybody else has a mindset - our mindset is just “the right thing.” But seriously, what are the unwritten rules in software development?

And it’s not even just Ops or DevOps. There are a lot of mindsets in the world, and developers are just one of many.

If we’re the fish in the bowl, what does the water look like?

And what would the opposite look like? If software developers get our superpowers from this mindset, what superpowers do other folks get from very different mindsets?

Developers are In Love with Problems

In the old The Tick comic, another superhero offers to team up: “working together, in a few months we could eliminate crime from this city completely!” The Tick says, “I don’t want to eliminate crime! I just want to fight it.”

He might have made a fine software developer.

When you show a developer an ugly, sticky problem that wants a complicated software solution, we start to salivate. In job descriptions, we brag to each other about “interesting problems to solve.” And when we say “interesting,” we mean technically difficult, not “relevant to the world at large.” We use different phrases for that.

We don’t want to eliminate people’s problems that can be fixed with software. We just want to fight them.

This gives us simple superpowers: motivation and skill. We love to struggle mightily against problems, and it makes us strong. It means we love to practice. We don’t need a reason to solve a problem with software. We just need time and a chance to work. We want to solve a problem, just because it’s there.

What does the opposite superpower look like? Look at business folks. Show them a problem they can tiptoe around and they’ll avoid it. Show it to us and we’ll fight it. We get the skill increases from fighting a thorny problem, while they get the ability to rapidly move on to the next problem without a fight. They may have problems later because they didn’t really solve it. We may have problems later because our solution is imperfect, and that adds size and complexity — avoiding a problem is often more reliable than mostly solving a problem.

Operations folks often have a related not-like-developers superpower: a talent for using bubblegum and baling wire to jury rig a not-really-solution that works. If you’re a developer, I don’t need to tell you how this can go wrong. But if you’ve done much operations, I don’t need to tell you that the same approach can often work well enough for a long time and save a lot of effort. It’s an especially good superpower if you’re not sure your whole product or company will work out — the bubblegum and baling wire solution is often good enough to last until something else kills the whole current attempt and you have to rebuild.

Developers are Optimistic about Eventually Fixing All the Bugs

We don’t necessarily believe that this next bugfix, or release, will fix all the bugs. But we believe if we keep working, we’ll eventually get something that does the right thing. We believe it will take a large but finite amount of work to get to “really quite good.”

Like the previous section, this is good for our motivation. Like the previous section, it often means we’ll wade into trouble for the sheer love of the fight.

We’re not always right, of course. Some tasks are impossible — look at the Halting Problem. Some tasks are presumably possible but far too difficult for humans to solve yet, such as the Turing Test or other forms of Strong Artificial Intelligence. Sometimes we wade into something that is, from our current point of view, absolutely impossible.

But the flip side is that we can often solve things that looked impossible but aren’t. That’s the developer superpower gained by this point of view.

The opposite superpower, shared by OpsFolk, Business Folk and very senior developers, is avoiding fights too difficult to be winnable, at the cost of occasionally tiptoeing around a fight they could have won at great cost.

You’ll note that startups often want younger, less-experienced developers specifically for this reason. They’re looking for problems that look impossible, but aren’t. If you throw younger developers at the problem, they’ll try very hard to do the probably-impossible. If you throw experienced, sadder-but-wiser developers at the problem, they’ll often avoid the impossible in favour of the hard-but-clearly-possible.

Is that good? Like everything here, it depends what you’re doing.

Developers Quietly Contemplate and then Turn the Model Into Code

Skilled developers are often masters of creating complex mental models of a problem. They’re also very good at lateral thinking and simulating a problem in their head. Eventually they can become excellent at checking the real world to find out where their model is right or wrong.

They can also be almost frighteningly detached, listening to complaints and problem descriptions but barely reacting as they run through their mental models and update them. This can be reassuring as you’re designing a new system, and frustrating if you’re trying to see if the developer understands how bad your problem with a current system is, and how much you need them to fix it.

All of this tends to require a lot of quiet, stable, controlled time to think through the problem and examine it from many angles. That examination doesn’t usually work if the developers have to deal with interruptions, bug-fix requests, production outages and other problems.

So developers often work hard to avoid interruptions. That can involve a bug-fix team member to keep the rest of the team from being interrupted, or handing the work off to operations people who handle outages, or working late at night without other team members interrupting, or scheduling blocks of “maker time” to think about a problem for a long while without communicating with other people. There are many other strategies with this end goal.

The developer superpower is in design, building and debugging of complex systems: by intense focus, a developer can be effectively smarter, and more capable of creating interesting software systems.

The opposite superpower, common to Operations folks, allows them to be highly interruptible and resilient, able to do their work despite annoyances and unexpected occurrences. They don’t have to like it, of course. But as a rule they arrange their work-lives to handle it better. It’s possible to arrange your work-life so you don’t have to be smarter.

Developers Hate Repetition

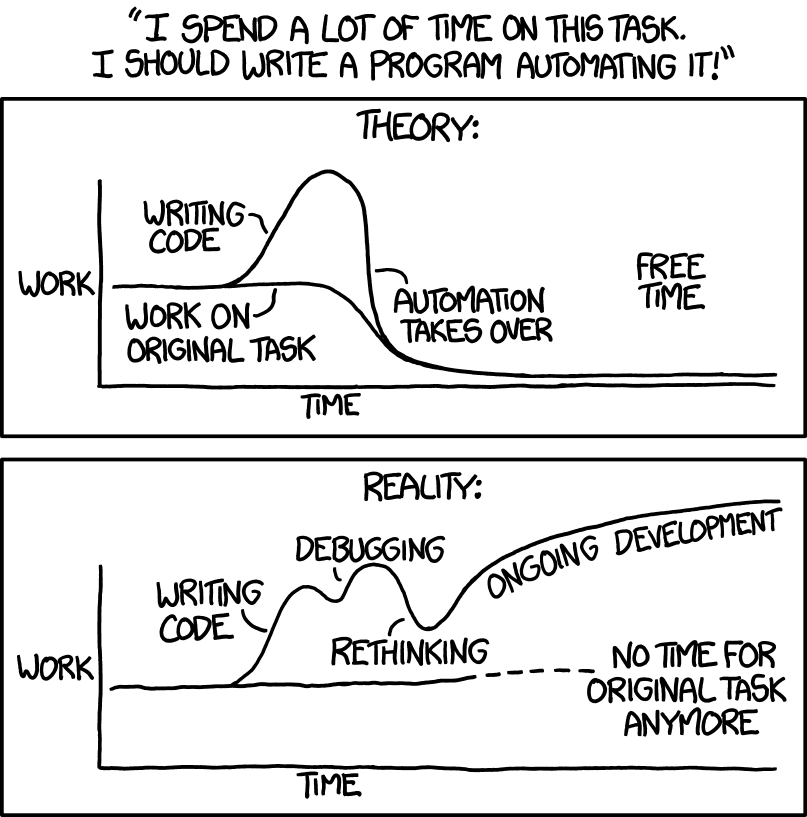

We hate repetition, and we love automation. Sometimes I wonder if we don’t just have seriously wandering attention — automating may be harder, but at least it’s new. Often we’ll try to automate a task long past the point where it will save us any time. This can be good for our skills, or for solving a larger problem for other people. It’s usually bad as far as our own personal free time.

We also tend to strongly favour re-use of solutions. That can be great: of course re-using something that works is a good idea, especially when it solves a real problem. Unfortunately, it can also lead to treating problems as the same even when they’re not:

"Hey, use this tool to solve that problem."

"This isn't the same problem."

"Eh, close enough."

It’s one reason we often get along poorly with designers and technical writers. Designers usually need to recognise that the same basic functionality (e.g. word processing) is often used in multiple different ways, leading to multiple solutions that could be “the same”. And so a set of tools that are basically similar (e.g. Apple Pages, Microsoft Word and the authors’ tool Scrivener) are often treated as inefficient and repetitive when in fact the “same” functionality (word processing) does different things in the three cases.

As a designer said to Bill Gates without much effect: a drinking fountain, a sink and a toilet all have to squirt water and drain water, but that doesn’t mean that we should just use one object for all three.

Sometimes a developer is right: using the same solution for many things can be powerful, like how the web browser has supplanted a lot of other bad interfaces. And sometimes trying to use the same solution for very different things results in a bad kind of over-efficiency, like when a spreadsheet solution keeps anybody from trying to make something better.

The opposite sensibility, favouring repetition, gives different superpowers: a designer often favours repeating functionality so that the same thing can be tweaked slightly for slightly different use cases — like having a separate ‘redundant’ camera, music player and fitness tracker even though you already own a smartphone.

An artist favours repetition for diffrent reasons: they are trying to perfect the expression of the thing (e.g. how to paint a face) rather than do it once “perfectly” and stop. Thus, software developers get the “efficiency” superpower, designers get “excellent suitability-for-purpose,” and artists get both “great skill in expression” and “extreme specificity to purpose.”

Developers Hate Obvious Inefficiency

Related to automation: developers hate certain kinds (not all) of ineffiency. Why do something over six months if there’s a way to do it in two days? You can see this in the vast array of “Learn X Programming Language in 48 Hours” books, when realistically you know it will take far longer to do anything useful. Similarly, there are many, many short tutorials so that we can avoid ‘wasting’ a long time reading a full-length book on the problem, language or library in question. The promise of learning improbably fast makes us happy. A few of these tutorials even work well, though long study works better, as a rule.

In some cases, this bias toward the instantaneous can be good. If you can find a domain where you learn fast and work fast, you can improve ridiculously quickly. The software startup “rocket ship”/“hockey stick” trajectory is a direct result of finding fast learning and improvement, and working hard to keep it happening fast. Occasionally a developer can become an “instant expert” and very rapidly master a new area if they can just keep from slowing their learning with one distraction or another.

These instant-expertise cases are rare and you can waste a lifetime of reasonable opportunities in looking for them. It’s like if you avoided opening a bank account to spend it all on lottery tickets; recognising a winning lottery ticket is good, but spending your whole life looking for one is bad.

Yet looking for large advantages and then taking advantage isn’t a bad thing.

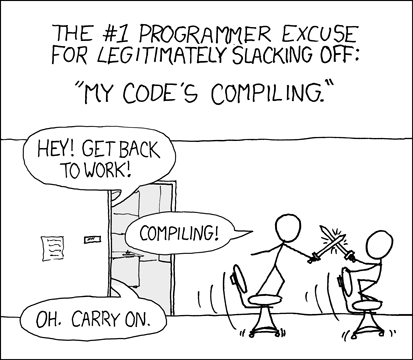

Oddly, we don’t mind non-obvious inefficiency. Developers cheerfully put up with long compile times because they feel “busy” in a good way. If the test suite is running we’re often happy and we feel productive. These are both often true even if you could speed both up by 10x with some work. But the time spent feels “efficient” and “productive” even if it’s not actually a quick route to progress.

Developers often hate being idle, because that’s obvious inefficiency and it feels unproductive. We hate status meetings where our progress is slowed for somebody else’s benefit, which feels like inefficiency. And we hate “waiting to respond” situations where we’re assessing a situation and don’t know what’s happening yet. To be fair nearly everybody hates those situations, but developers often label them as “inefficiency” even when they’re not.

This one doesn’t have an obvious opposite, though it has several important contrasts. Operations folks often like tinkering and fiddling to get a feel for a system, and to “just” learn. That’s a powerful skill, and it requires tolerance for not knowing what the goal is (yet.) Artists and designers are often willing to play and dabble before jumping into a project, just to get a feel. In my experience, that’s much rarer for software developers, though I don’t know why it should be. Businesspeople hate inefficiency that obviously costs money, which is a bit different from developers, though there’s overlap.

Developers Get a Huge Kick Out of Arcane Knowledge

Developers love knowledge and trivia in our areas of focus. What arguments does a particular function in the standard library take? How does a particular JavaScript framework handle HTML rendering? In C++, is a template-based approach faster than macros for this problem? We’ve mostly broken the habit of using these as job interview questions, but we did for many years. And it’s still the kind of thing developers do to posture when they get together in groups.

Knowledge is good. Uncommon knowledge is better. Knowledge whose specifics can barely even be explained, is best. For an example of “can barely be explained,” step into your favourite debate about exactly what a Monad is and why it matters. I’m not trying to pick on Monads, Haskell or Functional Programming — Object-Oriented Design has its Law of Demeter and SOLID principles, C++ has template code, Ruby has metaprogramming. We love our subtle arcane knowledge.

This tends to favour academic knowledge over skills and practice. Demonstrating your mastery of a practical skill is harder, especially in the middle of an Internet flame war. Being able to do Object Oriented Design really well is only impressive if the other person’s skill is close to your own — a rank novice may simply not understand that what you are doing is impressive. However, being able to parrot back all the SOLID principles and what they mean can be verified via Google, so the simple trick is better for posturing than the complex and well-developed mastery of a valuable skill.

This bias also favours facts and trivia over tuning and improvement for the same reason. You can show that a particular piece of optimisation works, but you can’t easily show how difficult it was to come up with. But an Internet game of Trivial Pursuit or Debate Team can make you look good, in a “winning the pointless debate” sort of way.

The way developers keep score with trivia and challenges is a bit different from business folks, who keep score with money. And it’s different from artists and designers, who do use practical skills for bragging via their portfolios. I’m not sure what the equivalent for Operations folks is, though it might be war stories.

Developers Love Complexity

I’ll wait a moment for all the Clojure developers to protest mightily before I continue. Take a breath! Okay, let’s get started.

Developers try to impress each other with complexity. Here’s all the cool stuff this framework does for you automatically! Here’s this powerful library and how many complicated things it can do! Here are all the options that are supported! Look at how well this programs handles scaling up to huge numbers of requests! Look at all the libraries that are integrated into this! Look, I used MongoDB and I can run this on ten hosts with automatic load-balancing!

Even the kind of “simplicity” we favour tends to have many tons of freight of mental models. Pointfree style? Mathematical abstractions like Monads? Simple-looking code where the complexity is hidden by annotations or metaprogramming? In some sense, these are simple. In another, saner sense, they really aren’t. “Simple once you’ve taken weeks or years to understand the model” is different from the word “simple” as used in other professions. For what it’s worth, a mathematician might agree with this definition of “simple.” But I suspect they’d use the word “elegant” instead.

Actual simplicity, where we actually avoid thorny problems, tends to be frowned on by programmers. This is a close relative of developers being in love with problems: avoiding problems when it isn’t necessary to solve them is treated as cheating, even though it’s a really good idea in most human activity. You’ve probably heard the joke/story about Space Pens — “NASA spent $165 million developing a pressurised pen that could write in space; the Russians used a pencil.” That punchline is exactly the kind of solution that software developers make fun of. We may occasionally use the “simplicity is good” argument to take down a blowhard colleague’s bad solution. But a complicated, multi-part solution is generally treated as proof of intelligence and hard work.

Conversely, somebody who tends to come back with genuinely simple solutions by finding a way to step around the complexity is often treated as cheating, or not trying, or not a “real developer.”

This is another reason non-developers tend to see us as being obsessed with trivia and arcana. One of the easiest ways to add complexity is to tack on more extra bits of trivia and arcana. “Look, I also made it read email!”

Here’s an example of a developer (Sandi Metz) swimming against the current of this heading. When she presents a very simple solution that turns something hard into something easy, she finds that nobody else tried that. “Why did this occur to me and not to others?” she asks. Because a solution like that (decompose the problem into two simpler steps, run them consecutively) is often a solution where we look for excuses to disqualify it - “oh, but that’s less efficient” (there’s that word again.)

Developers are Highly Specialised and Believe Things They Don’t Understand Are Easy

Most people believe that what they don’t know is either trivial (“why don’t you just…?”) or impossible (“oh, I could never learn to paint like that!”) That’s not particularly specific to developers, but developers are people, and mostly they share this very normal, very human trait.

And in fact, while those sound like opposites (trivial vs impossible,) in some sense they’re the same thing. “Oh, you can paint like that because you’re a natural artist” is often the implication — it may be impossible for me, but it’s trivial for you. That’s why people don’t like the common answer from artists (“it just takes lots of practice.”) That answer would turn it into a skill which other people could have, but it would take a lot of work, and the artist does have, but only because of a lot of work.

Neither the trivial and the impossible demand your respect. A skill that is merely very difficult and very expensive does demand respect. So “trivial” and “impossible” are both convenient and very human ways to trivialise others’ accomplishments.

This is, again, not specific to developers.

Here’s the part that’s more specific: developers tend to be highly specialised. Our skills tend to require a lot of time to learn, and we tend to learn a lot of different computer skills - multiple programming languages, multiple libraries, at least one operating system and so on. We are often computer hobbyists as well as computer professionals.

There’s a strong tendency for “computer stuff” collectively to eat up a big chunk of our lives.

That means there are more normal human skills that we don’t put a lot of time or thought into, and which we therefore assume are either trivial or impossible.

If you can cook a bit, you tend to respect an excellent cook and understand the effort they put into becoming one. If you play tennis, you tend to respect an excellent tennis player.

Developers have a strong tendency to ignore random non-computer skills and hobbies in favor of computer skills and hobbies… Which leaves them less respectful, as a group, of skills like knitting and golfing that have no computer component, and which aren’t frequently practiced by developers.

https://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/physicists.png

This is also the origin of “but that sounds easy, why don’t you just…?” as a response to other major fields of study.

This is an interesting one to contrast, because artists sometimes have the same problem. They’re consumed in their own skills and may not have a lot of interest or respect outside that world — not always, just like developers, but frequently, just like developers. By contrast, Operations folks often have background with more “random” skills, and businesspeople almost always require a huge range of skills in small amounts. A businessperson may or may not respect skills that don’t make money, depending. But they tend to understand that developing those skills is difficult and takes work.

Developers Want There to be a Right Answer

One major difference between junior and senior developers is that good senior developers have slowly become bitterly resigned to the idea that everything is a tradeoff. Every tool, every techique is good for some things and bad for others. At best, a particular tool or technique may be clearly the right one for the job you’re doing. And even that becomes more dubious as they gain experience.

Charity Majors recently talked about getting the “sadder but wiser” perspective of a senior developer. Yeah, that.

Why is it so hard for us to do that? Because we want there to be a right answer. We want there to be a “best.” We’ll defend our programming language, our text editor, our libraries as the best against all others because we really, really want there to be a best, not just an unlimited number of different “maybe best for this specific situation” tradeoffs.

If there is a best, our job is, perhaps, simple. We can use the best thing. If there is nothing but ten thousand subtle tradeoffs then we’re responsible for somehow navigating that huge and horrible mess for every project. Junior developers seem to find this reality too harsh to face, while senior developers seem to grudgingly work around it while trying not to look directly at it.

We all have our cross to bear.

Computers are highly deterministic. When we give them instructions, they have a very strong tendency to do the same thing in response, over and over. This is especially true when things are working well, and for beginner tools. As a result, people who find this enjoyable and comforting are especially likely to become developers.

And then, as it turns out, they step into a field with no right answers, only tradeoffs as far as the eye can see.

How can you not sympathise?

Worse, the farther they advance in their discipline, the more their job is dealing with humans instead of computers. The world is not a fair place, for developers or anybody else.

But at heart, we really want there to be right answers. We really wish there were right answers. We argue vehemently that just in this one specific case there are totally right answers and if you don’t see that, you’re a fool.

We’re unquellably optimistic at heart, is what I’m saying.

As a side effect of this, we really love getting a gold star. Those same early-career tools that give simple, repeatable responses? We became developers partly because we love the puzzle of getting them to do what we want. And after trying hard for awhile, we get it right. And the computer — our tool, our authority, the judge of whether we did it right — gives us a gold star. It does the thing we wanted it to do.

Programmers like right answers, and like gold stars. The early part of our career arc almost requires it.

And then we step out into the muddy world of human needs and unreliable systems and jobs, where nothing is clearly exactly right or wrong.

There’s no justice in this world. Unless it’s some kind of poetic justice, and I don’t want to think too hard about that one.

What superpower does this give us? It keeps us looking for that right answer, long past when a saner person would give up.

What’s the contrast here? Well, artists are often working for their own gratification. If they draw a thing and they like what they drew, they give themselves a gold star. That’s probably healthier, honestly. And they tend not to believe in specific right answers, since more of their discipline is based on being different and creative. Excellent small-company business folks do neither one, in favor of satisficing (doing 20% of each thing so that everything is adequate and little is excellent.) That means their superpower is being able to juggle far, far too many activities at once. And while Operations get a different set of powers - the power of “good enough,” where they can do most of a thing and then stop, which is very powerful. And the power of tuning and tweaking, where they don’t believe a system can ever be fully good enough, but they’re often happy to stop working on it when something else comes up.

Comments